Reporting For Duty

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Quick Links

Categories

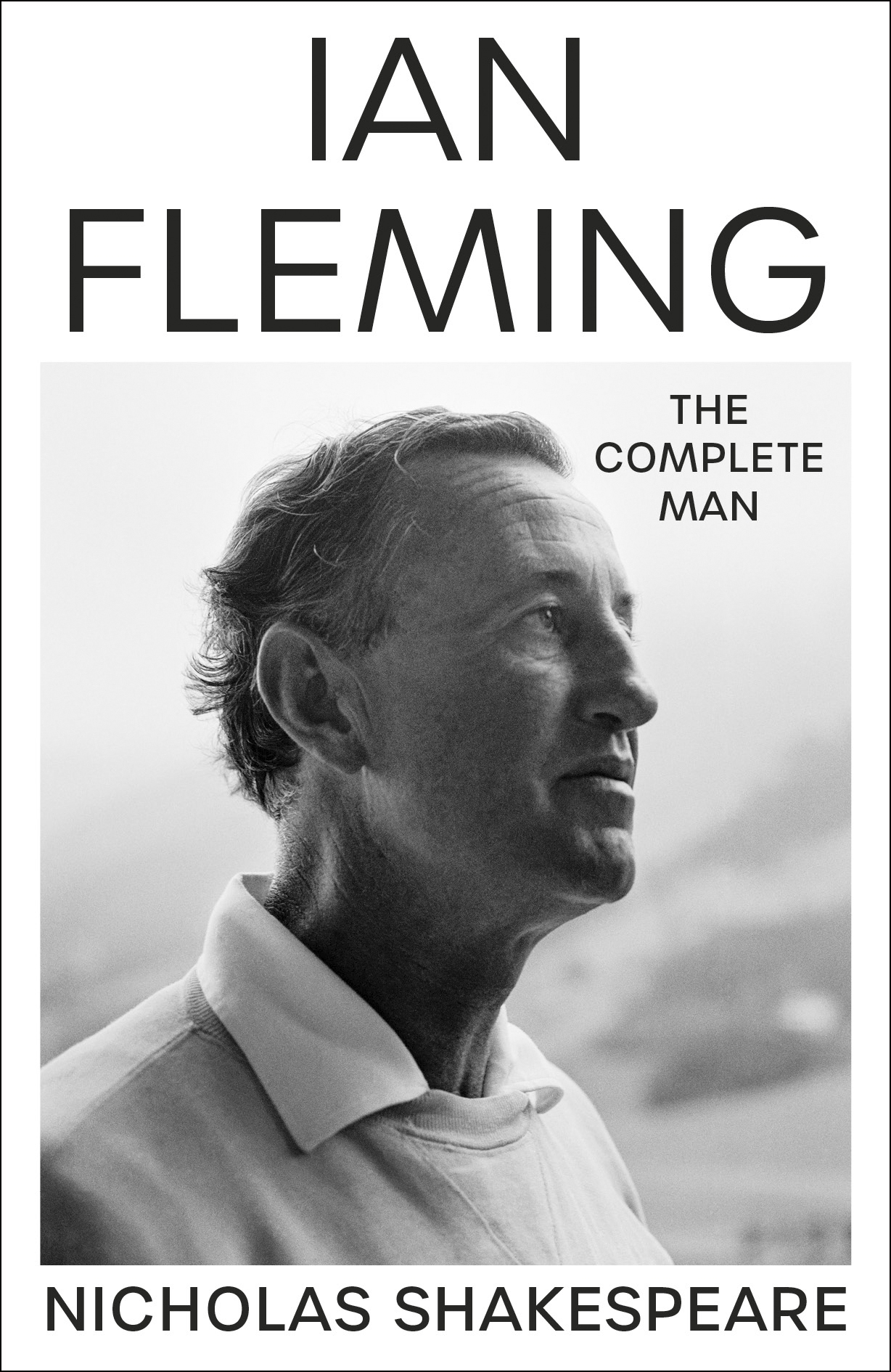

'Ian Fleming: The Complete Man' by Nicholas Shakespeare

Red_Snow

Australia

Red_Snow

Australia

Release Date: 3 October 2023

A fresh portrait of the man behind James Bond, and his enduring impact, by an award-winning biographer with unprecedented access to the Fleming Archive.

Ian Fleming's greatest creation, James Bond, has had an enormous and ongoing impact on our culture. What Bond represents about ideas of masculinity, the British national psyche and global politics has shifted over time, as has the interpretation of the life of his author. But Fleming himself was more mysterious and subtle than anything he wrote.

Ian's childhood with his gifted brother Peter and his extraordinary mother set the pattern for his ambition to be 'the complete man', and he would strive for the means to achieve this 'completeness' all his life. Only a writer for his last twelve years, his dramatic personal life and impressive career in Naval Intelligence put him at the heart of critical moments in world history, while also providing rich inspiration for his fiction. Exceptionally well connected, and widely travelled, from the United States and Soviet Russia to his beloved Jamaica, Ian had access to the most powerful political figures at a time of profound change.

Nicholas Shakespeare is one of the most gifted biographers working today. His talent for uncovering material that casts new light on his subjects is fully evident in this masterful, definitive biography. His unprecedented access to the Fleming archives and his nose for a story make this a fresh and eye-opening picture of a man who lived his life in the shadow of his famous creation.

^ Back to Top

The MI6 Community is unofficial and in no way associated or linked with EON Productions, MGM, Sony Pictures, Activision or Ian Fleming Publications. Any views expressed on this website are of the individual members and do not necessarily reflect those of the Community owners. Any video or images displayed in topics on MI6 Community are embedded by users from third party sites and as such MI6 Community and its owners take no responsibility for this material.

James Bond News • James Bond Articles • James Bond Magazine

Comments

James Bond is the world’s best-known spy hero — but the life of 007’s creator was more like a triumph of failure

Ian Fleming was the most globally influential British writer of the 20th century. You disagree, citing Waugh, Orwell and Uncle Tom Cobley? In Nome, Alaska, or Ulan Bator hardly a sledge dog has heard of Orwell, but the entire population knows James Bond.

Yet his creator spent the first 44 years of his life amassing a remarkable record of failures. He left Eton prematurely, fled from Sandhurst, flunked the Foreign Office exam and threw up a promising journalistic career to become an unhappy stockbroker.

While a whizz with women, he seemed incapable of sustaining a relationship. When once he did so, with his Swiss lover Monique Panchaud de Bottens, he was forced to break off their engagement because his appalling mother, Eve, gave her the thumbs-down.

...Nicholas Shakespeare, who wrote the definitive study of Bruce Chatwin, has compiled a monumental record of Fleming’s life: every lover, friendship and (almost) round of golf. The completeness of the book is beyond doubt, although its subject was a heroically incomplete human being.

...Shakespeare convincingly shows that Fleming, like many romantics and adventurers, found a personal fulfilment in wartime. But I cannot accept his claim that his man became an important player in the intelligence community and was mistreated by being denied a decoration in 1945. Evidence from both war and peace suggests that while many people found Fleming entertaining, few took him seriously.

Until, that is, he became a global bestseller. How did he do it? How did he, in the last 12 years of an abbreviated life, invent a world-conquering superhero, boosted latterly by the terrific movies of Harry Saltzman, Cubby Broccoli and Sean Connery, which added jokes to the humour-free stories?

First, the flipside of Fleming’s delusional make-up was that his narratives were suffused with absolute belief in his ludicrous plots and characters. Next, he was a descriptive writer of the highest gifts. From Russia with Love, especially, still reads superbly. When I research real Russian spies, I am struck by how well Fleming caught the spirit and language of such brutes. And Bond, like the entirely comparable Sherlock Holmes, suspends our disbelief to seem capable of single-handedly saving the Empire.

His creator conveyed a sense of authority, even omniscience, that was often spurious — for instance, about guns — but fooled most of us. He wrote as a supposed gourmet, but the food at Goldeneye was notoriously awful. Fleming’s fantasy club, Blades, hardly sounds inviting when such arch-villains as Hugo Drax were members, although I suppose that is likewise true of White’s.

Fleming brought to his tales immense experience of women, although whether he really liked them, as distinct from enjoying sex, is debatable. His 1952 marriage to Ann Charteris, a social lioness with a predator’s taste for human raw meat, brought misery to both.

...The last lines of Shakespeare’s book describe how, after Fleming’s 1964 death from a heart attack, aged only 56, a friend discovered the pages of a new, unfinished Bond story and excitedly showed them to his widow. Who promptly chucked them on the fire.

Shakespeare leaves no future biographer much to discover. Fleming’s place in history is assured. But after viewing his train wreck of a life, no sane person could envy Thunderballs, as Cyril Connolly and Ann Fleming sadistically mocked him.

Seems reviewer Hastings plus author Nicholas Shakespeare have some unpleasant items to share, not a surprise. And not saying they're wrong to do so.

Even with these short excerpts, revealing.

Thanks, as always!

After a long summary of Fleming's life The Economist concludes:

Fortunately The Economist's critics are anonymous. I hardly need to point out that plenty of Bond films are "very much of their time—and not in a good way."

The review from the Financial Times is considerably more intelligent and pairs Shakespeare's biography with a recent one of John Le Carre. Some excerpts:

The Telegraph gives Shakespeare four out of five stars:

Max Hastings, who'd reviewed the book for the Sunday Times, revisits it for the Washington Post, in an article titled "Did James Bond Have a License to…Globalize?":

Robert McCrum, who had written positively about Fleming during his stint as the Guardian's book critic, has good things to say about Shakespeare in The Independent:

Raymond Benson has read it, and given it his approval.

An essential item in my ‘Desert Island’ library would be The Times Literary Supplement, dropped to me each Friday by a well-trained albatross. If forced to produce some reason for my affection for the journal, I would lamely say that I am nearly always interested by its front page article, by the letters, although there are not enough of them, and, being myself a book collector, by its back page of bibliophily. But, less lamely, I would praise the anonymity of its writers and reviewers which surely lies at the root of the unshackled verdicts that are, sometimes to the point of splendidly savage denunciation, to be found in the T.L.S.

(Thanks @Revelator )

I recall the first sentence of that quote being put as a footer at the bottom of issues of the TLS back in 2008, during Fleming's Centenary year. It seems to me that since those days the TLS has taken a retrograde step in its reviews of Ian Fleming.

Not exactly wrong, but I'd like to see this same energy invested into also attempting to find redeeming qualities about CR and Bond for a modern audience, because there's clearly something that still speaks to audiences today, for a full critique to be met.

Do we want to discuss Fleming's ultimate significance in the modern Bond's world? Is he really that important today, if you have to twist his work into something he would hardly recognize for a modern audience to buy a ticket? It's an interesting suggestion. I would point to CR the film to say Fleming still lives on screen, but I would argue by NTTD we are far from Fleming's vision for the character.

Also, as a car reviewer, expensive cars are not quite cancelled! At least not among their target market and audiences. That is laughable to suggest. I am also interested in @Dragonpol 's perspective regarding editor oversight at publications. Would be happy to dm you about it as I'm an editor! Sometimes I do look to my publication's past opinions on stuff like branding and marketing etc., but we try to keep reviews somewhat personable to the writer and have been moving away from a collective voice in our articles. That can lead to some strong headlines and opinions, but I feel my job as an editor should be to check that before it heads out of the door, so I agree that this pub should be a little more aware of its history and record in order to respect its audience.

I don't think the TLS has had a positive word to say about Fleming in at least three decades. The review of Lycett's biography was also full of distaste for Fleming. As for the current reviewer, he's listed as the editor of anthology of 15th century poetry...which makes you wonder why the editor chose him. Why not someone like Jeremy Duns, who is a spy novelist and historian of spy novels?

As for the reviewer's objections to Casino Royale, they're easily disposed of. Implausibility? Better arraign Hitchcock and everyone else who's made a thriller as well, since the genre depends on implausibilities. As Fleming wrote at the start, assassinating Le Chiffre would make him a martyr, so better to send the service's best gambler to bankrupt him and force Smersh's hand. The appearance of the Russian assassin, far from being "implausible," had been prepared for since chapter two, when we learn Smersh will certainly kill Le Chiffre if he can't return the money he embezzled.

Nor is the role of Vesper "unclear." She's been sent as Bond's assistant, was chosen because she's a radio expert and speaks French, and works for the Head of the Soviet Station, who recommended the whole operation to begin with! Did the reviewer skip a few chapters? Nor is her suicide "implausible": she betrayed an organization devoted to hunting down and killing backsliders, she sent her old boyfriend to his death, and she knows she'd have no future with Bond after he learned she was a traitor. Suicide seems like a pretty plausible option!

Flat characterization? True, it's not deep, but why has the reviewer said nothing about Bond's speech on the nature of evil, his doubts about his job, and how he undergoes a character arc, threatening to turn from a "wonderful machine" into a human being, and then reverting at the end? And while some of the most engaged writing is indeed in the torture section, what about the gambling scenes, some of the most dramatic and compelling in the entire book? Or is all that beyond the grasp of the reviewer?

The reviewer suggests the appeal of Fleming, supposedly based in consumerism, has faded, thanks to "the historical, cultural and economic distance" that separates the modern reader Bond’s world. By the same logic, we should turn up our nose at the Sherlock Holmes stories, since those also have implausible events, shallow characterization, and take place in a world very far from our own. Look at all the distance between us and 1895!

But fixating on consumerism blinds us to larger facts. Fleming did not simply list whatever the most expensive goods of any type were. He picked what what he personally thought best or appealing, so the books are an idiosyncratic record of one author's mentality. Beyond that, "consumerism" was merely part of Fleming's larger fixation on objects and detail, which he relied on to give his novels grounding in the real world and suspend the reader's disbelief in more fantastic elements. This focus on detail, whether in operation of a card game or dinner at a casino, allowed Fleming to capture a now lost mid-century world just as successfully as Doyle captured the London of 1895. Part of the modern appeal is precisely in the presentation of a now-distant world. Again, all this seems beyond the reviewer's ability to grasp...

Yes, that bit seemed especially out of touch. If expensive cars are so politically incorrect, why is Bond still driving them in the movies and why are they still selling so well? Even Teslas, which sell like hotcakes, can be pricey. Another sign that the TLS editors chose the wrong reviewer.

While I wouldn't class Fleming as a great literary artist, I think Kingsley Amis got it right when he said we should place Fleming in the company of Doyle, H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne, and other classic authors of adventure and enchantment. Yet there are still parts of the intelligentsia that refuse to do so and attempt to reduce his work into dismissable components, or insist that the movies are far more significant. But the most important and influential Bond films, the first four and OHMSS, were close adaptations of Fleming, and even NTTD borrows elements from the books. Anyway, one bad review out of a chorus of otherwise good ones isn't a tragedy. We'll see how American critics handle the book, but I'm not expecting much from them.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m001tq7x.

***

...Today, they are probably the most enduring authors on decolonization, Fanon for and Fleming against...They saw the end of empire as a wrenching psychological event. Healing its wounds, both believed, would require violence.

...Fleming remained, to use Fanon’s phrase, “sealed in his whiteness.” His novels teem with outrageous stereotypes: Blacks are “apes,” Koreans are “lower than apes,” and the Japanese are a barely civilized “separate human species.” The thought of such people coming into their own was, for Fleming, alarming. The great powers will “reap the father and mother of a whirlwind by quote liberating unquote the colonial peoples,” one of Bond’s allies warns. “Give ’em a thousand years, yes. But give ’em ten, no. You’re only taking away their blow-pipes and giving them machine guns.”

It’s a fear that haunts Fleming’s novels. Supervillains of complex hues menace the world from breakaway spaces: islands, large ships, secret fortresses, newly independent countries. “Mister Bond, power is sovereignty,” Doctor No, a half-Chinese criminal with a Caribbean island, explains. It falls to Bond to restore No’s island to British rule.

This was imperialist escapism, and the more territory Britain lost the more Fleming’s sales grew. But Fleming struggled, amid success, to stay upbeat. In the final Bond novel, “The Man with the Golden Gun” (1965), written in the wake of Jamaican independence, the villains allude to a looming “big black uprising,” which Bond does nothing to forestall. He kills a Rastafarian (“He smelled quite horrible”) and forces some Jamaican women to dance naked. Yet he ends the book hospitalized, recovering from poison and, like [Anthony] Eden, “acute nervous exhaustion.”

...In the novels, Bond’s personal woes and Britain’s political ones are linked. They are resolved only when Bond, with his license to kill, rouses himself to dispatch the Empire’s enemies. This was Fanon in reverse: bloodshed as balm not for the colonized but the colonizer.

...Fleming wrote a terrible Bond novel from a woman’s perspective (“The Spy Who Loved Me”), and Fanon discussed Muslim women who infiltrated settler spaces...Yet, mostly, their protagonists were men, with women serving occasionally as props in men’s psychological journeys.

...Both authors redirected violence onto their partners: Fanon publicly struck his wife and Fleming practiced sadomasochism. And both saw women as complicit... “All women love semi-rape,” his lone female narrator explained. “They love to be taken.” After Bond kills Doctor No, his dark-skinned (yet white) Jamaican companion throws herself at him, demanding “slave-time.” Such passages are cringeworthy, but they weren’t misfires. Rape, torture, subjugation—this was empire, red in tooth and claw.

...Fleming also inserted references to the real-life C.I.A. director Allen Dulles, a known Bond admirer, into three of the books. Yet this flash of reality only highlights how much of Bond—the shark tanks, the loquacious villains, the endlessly up-for-it women—is consoling fantasy. Perhaps the largest consolation is the idea that, in the actual Cold War, a British spy would be allowed at the adults’ table.

...In 1962, the British, in a flurry of self-congratulation, allowed Jamaica to go free peacefully. Fleming insisted that Jamaicans still carried the Queen in their hearts, but the gin-soaked ruling class to which he belonged washed out with the tide.

Thank you, I agree with every word! The New Yorker reviewer is not even a literary critic--if he was he might have been more wary of quote-mining, and of assigning comments made by fictional characters to Fleming himself. As you note, Matthew Parker's Goldeneye was far less heavy-handed and belitting in examining Fleming's ties to Jamaica and colonialism.

The reviewer's strategy of examining the Bond novels primarily through the lens of colonialism doesn't go terribly far in explaining their appeal. Bond might make Jamaica safe for the British in three books, but what about the rest, the majority of the books? You'd have to strain pretty far to present *Goldfinger* as a story about colonialism. It's very easy to say the Bond books are imperialist escapism, yet much less easy to account why they and the films were and are so popular outside the UK.

But the TLS and New Yorker reviews are valuable in reminding us that those who choose to chalk Fleming's appeal down to a single factor, whether commercialism or colonialism, are missing the bigger picture.

Pico Ayer in Air Mail praises the book:

James Parker in the Atlantic, who wrote contemptuously about Bond several years ago, enjoyed Fleming's biography but couldn't resist getting in a few digs at the subject and his work:

Anna Mundow in the Wall Street Journal is very positive:

Please, let me know.

;)

A Google Lens search shows the photo comes from this webpage and it is presumably Fleming in his RNVR uniform during WWII:

https://www.ianfleming.com/james-bond-war-years/

That of the uniform and that it was during WWII is something that can be appreciated, that is very clear. I was asking for more information about the place, time or circumstance of the photograph.

PD: I had already used Google Lens before asking here.

;)